by L.P. Lee

The closer I get to the island, the more of a dream Tokyo becomes. The obelisks of high glass, the polished people, their nails and shoes so clean. The neon canopies, the subtle dishes, the cab drivers with white gloves on their hands. I leave it behind on the train ride down. Down to the fishing town with its immaculate streets and kindly grandmother, who hosted me in her ryokan and made me a breakfast of rice and fish. Now the fish scatter before my boat, clean waves break against the hull, and the green island looms ahead, rising from the horizon like an old god.

The closer I get to the island, the more of a dream Tokyo becomes. The obelisks of high glass, the polished people, their nails and shoes so clean. The neon canopies, the subtle dishes, the cab drivers with white gloves on their hands. I leave it behind on the train ride down. Down to the fishing town with its immaculate streets and kindly grandmother, who hosted me in her ryokan and made me a breakfast of rice and fish. Now the fish scatter before my boat, clean waves break against the hull, and the green island looms ahead, rising from the horizon like an old god.

Our boat hurtles through the sea. Sounds surround us: the roar of the engine, the whipping spray, the cackle of birds overhead, but my heart beats loudest of all. A drum-beat, rhythmic in my blood; a constant drum, a war drum.

The waves crash and I remember:

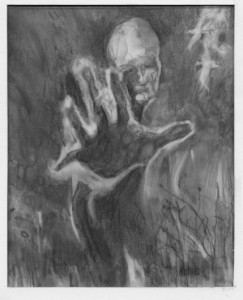

His face and body, so white. White paint on his unclothed skin. His bald head, white as a peeled egg. He squats on the floor, except you cannot see the floor. It is a black space, maybe a black sea. The black space surrounds him. He sits hunched over, head bowed, cradling his knees against his chest, rocking.

Slowly he lifts his head in an unnatural movement. The face reveals itself, eyes wide, staring with the blankness and malleability of a baby. The mouth hangs open, spittle on the chalk white lips. He begins to grin. Spit oozes over his chipped white teeth. Close up, into the emptiness of his eyes, or are they holes? Holes torn into white paper, and on the other side is a black space, empty as the space that surrounds him.

The sun and sea dazzle; I raise my hand, shield my eyes from the sight. The island looms closer.

“She’s seen us now,” the captain shouts.

I lean forwards, plant my hands on the boat’s ledge only to sharply withdraw. I turn up my palm to find a splinter has pierced my skin.

The island jumps closer. When I look up again, the trees are now clearly distinguishable. The black volcanic rocks jut from the shore.

It is a small island, a Pluto of the sea, empty of people.

As our boat approaches, the captain tries again to sway me. “What research can you do here? There’s nothing to see.”

“I just want to understand.”

The beach ahead is pristine; it seems like a paradise. Waves lap at the shore, birds swoop overhead.

But the captain’s concerns seep into me. Perhaps there’s something about the island, like they say, something darker than what meets the eye, lurking just beneath the surface. But I can’t let my imagination be provoked, and besides, I won’t let myself turn back now. I’ve been working on this project for months, and there are a few questions that remain, that will wrap up my research on Kaita Morimura.

Gradually I’ve chipped away at the mystery that surrounds him, unpicking his background and gaining insight into his thinking. Now I want to see where Morimura spent the last years of his life, secluded away from the world; see the writing that he etched onto the walls of his solitary home. I want to understand why the other island inhabitants fled from him. What was it about him, his death, that caused the island to become deserted?

The roar of the engine dulls to a throb. The boat bobs in the water, keeping its distance from the shore. The captain frowns at the green trees and volcanic rocks. His face, tanned a dark nut-brown, betrays a look of apprehension.

Slowly we approach the dock. The wood is not in good condition; parts of it have fallen into the sea.

The captain moors the boat and helps me onto the pier. His hand is weathered, his manner firm and gentle. His physical presence has been sculpted by a life at sea; eyes used to looking across vast distances rather than small, confined spaces, and a way of standing and moving that seems accustomed to the rhythm of the boat.

My own body has atrophed from a life of written words. My muscles are soft and underdeveloped, my stature is slight. I wouldn’t be good at lifting heavy objects. My skin is pale from university lecture halls and from working indoors. While the captain has a sense of energy spread evenly across his body, all my energy is concentrated in my head. I get headaches often; my tensions reside there too.

“You’ll be all alone,” the captain says.

I smile and tap my camera. “I’m not alone.”

He smiles too but there is concern in his eyes. I begin to make my way across the pier, onto the island.

I’m wearing sturdy boots and a rucksack. In the rucksack I have a notebook, a tape recorder and a collection of tapes.

On one of the tapes is an interview with a dancer who knew Morimura. I replayed it this morning, over the breakfast of rice and fish. It went like this:

“Sometimes when I looked into his eyes, I felt that there was nothing on the other side. Just an emptiness, like his face was a paper mask, or his eyes were holes into outer space. Black and cold, empty of other people.

I thought it was because of what had happened. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, people didn’t really understand. They thought that the survivors might be infectious, that they wouldn’t be good employees because of their ill health, and that they wouldn’t make good marriage partners because of the risk of deformed children. The survivors were called hibakusha, ‘bombed persons’.”

A bird squawks above me, in the trees. The sun is blinding; I feel its summer heat on my face and neck. But the sky is a beautiful blue.

The boat is now far away. The captain bobs disapprovingly in the distance.

There is a narrow dirt track that disappears into trees. I follow it and am swallowed up by the forest.

“He came from Hiroshima. Survived the vapors but his family didn’t. Sometimes I thought I saw this in his dancing.

While he was with us, he was invited to put on a show to commemorate Hiroshima. But he refused.

There was a businessman called Mr. Tanaki. He came out of Morimura’s performance looking very shaken. He thought he could launch Morimura, and reach a lot of people around the world. Never let people forget.

But Morimura didn’t even say no. He just ignored the offer. Went silent for a long time. I don’t think he spoke to any of us for a few months. Just ate with us, drank with us, and danced. But it wasn’t the same after that. Mr. Tanaki’s generosity would have been very good for us, as a group, and Morimura’s rejection caused bitterness. It started off small but gradually it simmered. Then there was Morimura’s big performance, and he left.”

The forest clears and there is a cluster of houses. They’re small, modern, white-washed houses. There’s a road behind them, leading to the other side of the island which is more developed.

A ginger cat slinks through the grass. It has a collar on but it looks skinny and malnourished. It moves nimbly, close to the earth. When it sees me, it freezes. The amber eyes fixate on my face. I crouch down and make coaxing noises, hoping it will come closer. But the amber eyes show no memory of ownership. In a moment it’s gone; dashed away, out of sight again.

Hesitantly I approach the houses and peer in through the windows. They’re all deserted.

I return to the dirt path and climb further up the hills, into the forest again.

The trees close behind me until I cannot see the white houses anymore. And beyond them, I can no longer see the sea, the bright waters and the little boat waiting. The canopy above my head grows denser and plunges me into shadow.

“Morimura had his own style. We never questioned it. Right from the start, Hijikata made it clear that the dance form was a reaction to structure and ‘fixity’. We were fed up with the rules of noh, and with the upright physiques of ballet, the Western ideals that were taking root in Japan.

Our way of dancing was a return to the essence of the body. Letting out what was in us, raw and unconstrained. In the 1960s this was a big deal. It was a new bodily aesthetic, overturning our postwar values of refinement and understatement. But it was also a return to an older kind of body.”

The forest clears again and I can see a house. A plain, modern, white-washed house like the rest, but much smaller. It’s a relief to see the sky blue and expansive again. I squint as the sun beats down.

My eyes have not adjusted to the bright clearing yet, but as the house comes into focus, I realise that the windows are broken.

This is where Morimura lived.

After his performance in Tokyo, his last performance and his greatest, he came here, secluding himself away from the world.

I am at the house. I can’t remember crossing the clearing. I circle the house in a daze.

On the walls I find a line of writing. I hope that it is Morimura’s hand.

I take a photo. My Japanese is not good enough to translate it here and now – I’ll save it for when I’m back on the boat.

I circle back to the front of the house, and try the door.

I look for a rock and clear the jagged glass that remains on one of the windows. I heave myself through the window and into the dark room.

The noon sun is directly above the house; little light filters in and again my eyes must adjust, this time to darkness.

“His last performance involved all of us, as a group. He’d never asked for our help before, and some people were reluctant at first. But we allowed him to choreograph us, and straight away, after the first session, we knew that it was going to be big. It’s still the most important piece of work that I’ve ever done.

We were very excited, and we put a lot of resources into publicising the show. We didn’t have much money, but with some help we rented a space in downtown Tokyo. Whatever we thought of Morimura as a person, we had faith in him as an artist. We knew that he was going to make an impact.”

The inside of the room is bizarre. Whoever broke the windows before me didn’t do it for theft. Everything is neat and orderly, everything except for the talismans…

Strips of white cloth fill the room, draped over the seats, hanging from the lightbulb, and strung up along the walls like bunting. They are embellished with stark calligraphic strokes; energetic black ink on white, calling for an expulsion.

These writings are ofuda. What happened here was an exorcism.

I take out my camera. The camera flashes are like lightning strikes, and they make me shudder. I feel as if I am waking up a tomb.

Quickly I look around for any notes that I must make. I want to get out of here as fast as possible.

I feel my heart pounding.

I search through the room, and find nothing.

My gaze drifts to the door.

I edge my way into the corridor, and there are talismans here too. They are like long ribbons of noodles, or a crowd of white birds whose feathers obscure my view, or stretched out ghosts.

I look up the stairs.

My heart pounds harder.

I creep up the stairs.

Why am I creeping? There is no one here.

I tread gently. I don’t make any sudden movements. The hairs on the back of my neck are standing on end.

I am holding my breath.

As I ascend the stairs, the question comes into my mind…

Do I really have the right to be here?

I’m on the landing now. There are no talismans here.

The door to the bedroom is open.

I creep in and find that there is another line of writing, this time on the wall above the bed.

I take a photo.

Again the lightning strike, and the sense of awakening.

I delicately look through the items in the room. Under the bed I discover a box. It is wooden and the size of a shoe box. Gingerly I lift the lid open, and find papers and a black and white photograph inside.

Kneeling next to the bed, I lift out the photograph.

It is of a man and a woman, with a small child between them.

They look at the camera with the unsmiling expressions common at the time for photographs. But the woman is wearing a dress that makes me confused.

It is a style of dress that comes from Korea. It’s a hanbok, a traditional Korean dress with a long-sleeved top and a bouffant skirt.

I put down the photograph and pick up the papers. The writing is in Japanese. It starts out neatly, and then becomes wilder. Morimura’s last words?

I feel very urgently now that I must leave.

But I spread the photograph and papers on the floor and lift up my camera. My grip on the camera seems unsteady.

Something compels me against pressing the shutter, but I fight against it. I press down anyway.

I take a photo and the lightning strikes again.

I spread out the documents, and take more photos. In that final flash, I see something. Under the bed…

Out, out! Down the stairs, the talismans are alive, a flock of white birds awakened whose wings flap in my face, obscuring the way ahead. Down, I almost trip on the last step, turn right, into the room where the talismans shake.

Through them, tearing away the white cloths that hinder me, towards the broken window. And out, falling onto the lawn outside, and stumbling across the clearing, blinded by the sun, until I am in the darkness of the forest again.

Down the dirt track I run, so fast and so panicked and on a declining hill that I risk losing my footing and stumbling. Hurtling down through the trees until I reach the next clearing with the small, white, modern houses. Past them, and down again. Finally, the sea! The boat bobbing up ahead, the captain reading a newspaper at the helm.

He looks up and sees me running. Immediately he is on his feet and coming towards me.

My feet clatter across the pier. He extends his hand wordlessly, and supports me back onto the boat.

I turn my face away from him and collapse and sit with my head in my hands.

Behind me, I hear the captain’s footsteps, the rumble of the engine starting. The boat begins to move.

I lift my head and see the shore receding, the island sinking slowly back into the sea, falling away on the horizon.

Around my neck, the camera hangs heavily.

*

Back in Tokyo, I disembark the night train and take a taxi. We drive through glittering streets and modern high-rises. The streets shine with fresh rain; puddles reflect the neon colours, the faces of people. I look out the window at the fluorescent monoliths rising high above.

The taxi driver wears white gloves and sits with a straight back. There’s a disciplined polish to his crisp, clean movements.

At the hotel, I sit on the narrow bed looking out at the view of Tokyo. It’s midnight. I fish the camera out of the suitcase and try to bring myself to turn it on.

But again that sense of resistance… Something stops me.

I put the camera down quickly as if it’s hot.

Instead I take out the tapes from my interviews and put on my headphones.

“On the day of the performance, the venue was packed. We had people standing all along the walls, crowding at the back, and kneeling on the floor before the stage.

We plunged the room into darkness with only a faint grey light on the stage. There was a lot of chatter in the room when the lights went out, but once Morimura began dancing, everyone fell silent.

He started off standing upright, elegant, and then gradually moved himself closer and closer to the earth, bent-backed and squatting, like so… All of his movements were slow but hyper-controlled.

When he reached the floor, there was a strong flash of light that illuminated everyone’s faces.

Then the smoke machines began billowing, and you could barely see Morimura through all of the smoke. But there he was, lifting his arms and legs and looking at himself as though surprised that he was naked.

He picked invisible shards out of the palms of his hands. Then he raised his mouth skywards, opening and closing it as if to catch precious rain.

We crawled in at this point, our whole group of dancers, surrounding Morimura with our ash-white bodies. Raising ourselves up, swaying with our arms held out. We turned up our heads to drink the invisible rain.”

I saw a photo of the performance. With their arms held out, they looked like zombies in an apocalypse.

I take off my headphones and pick up the camera again.

After that performance, Morimura disappeared. He resurfaced months later on the island.

I switch on the camera.

People tried to interview him. The performance had caused quite a stir. But he refused to talk to anyone. It didn’t seem like any kind of snobbery. He just wanted to vanish.

On the camera, the image comes up of the writing that was on the wall of his house. I flick through to the line of writing in his bedroom, and I realise that the two texts are the same.

Character by character I look them up on my phone.

The text reads: What is worse than a hibakusha? A zainichi hibakusha.

I write down the words and frown at them. My head begins to reel.

I move onto the photos of the documents, and decipher them. It takes hours of looking up words, checking the grammar and piecing the meanings together. But finally, after midnight, I am sitting with a messy translation in my hands, the paper filled with crossed out lines and rewordings.

It reads:

‘I was lying sprawled out on the floor of my room. I had just finished my night shift and was contemplating whether I had the energy to crawl into bed.

Suddenly, there was a flash of light… A strong, otherworldly light… I had never seen anything like it before. It was beautiful, but also frightening…

When I came to, I realised that I was in the middle of rubble. I had to scramble my way out of the building. I understood that a bomb had fallen, and as I made my way outside, I saw how lucky I was. The windows had blown straight in, and shards of glass punctured the walls opposite them. But I had only a splinter in the palm of my hand, and minor cuts and bruises.

The strange thing was that my clothes had vanished. I was naked! Where had my clothes gone?

By the entrance I found my friend Park Sun-il, who was badly injured and couldn’t walk. He was fourteen; two years younger than me, and he called me hyung, ‘older brother’. I felt ashamed that I was relatively unscathed.

I helped Sun-il out of the building, and then I felt a wave of nausea. I had to stop. Standing there, I couldn’t believe my eyes. The people on the street were burned from top to toe, and everyone was naked. Many people were holding their arms out, and I realised that it was because they didn’t want their burned skin to touch anything.

Buildings had collapsed and fires were everywhere. It was hot and difficult to breathe.

I carried Sun-il on my back. He was in a bad way, and he was desperate for water. I also felt an extreme thirst like I had never felt before. I decided that we should go to the river.

As we went through those streets, everyone was silent. No one made a sound.

Many of us were heading in the same direction, to the river.

I saw old women with peeling skin, young boys, mothers with their babies…

Schoolgirls with blisters on their faces… gathering around a police box, weak…

I heard sounds now… Young people, lying on the ground, calling for water…

In the distance I saw a tornado. It whipped through the streets, and everything that it touched was burned. Everyone tried to get away from it.

At the river, there were crowds of people. People were everywhere. Here there was a great commotion, and people crying out. More and more people were coming up behind us, crashing against us. The air was so hot that I felt my skin burning, and the water was a cool relief.

But as I dipped my head into the water, the water sucked me down, and I lost my grip of Sun-il. I tried to get out but the water was suddenly so strong. I thought for a moment that I would not be able to get out alive.

I heard Sun-il shouting my name, and I managed to grab hold of him, and drag us onto the other side of the river. I was so frightened that I hurried in taking us away from that scene before I stopped to think about what direction we should take.

I saw that many people were going in the same direction, and Sun-il said that it must be because they knew where a hospital was. So we joined them.

Soon it began to rain. The rain was black, and the raindrops were big. Everyone opened their mouths. They were all opening their mouths as wide as possible because they were so thirsty.

But the rain was sticking to everything. And it felt heavy, like oil. It hurt when it touched my skin. I begged Sun-il not to drink it, but he was so thirsty. He drank it.

I was beginning to shake from the effort of carrying Sun-il. Eventually we found a hospital, but it was overcrowded with people, and when they heard our accents, they knew that we were not one of them…

I didn’t know what to do. I seemed to be walking through hell. On the streets, there were not just bodies of humans, but also of birds, cats and dogs, even horses…

I took Sun-il out of the city, and tried to help him myself. I tried to stop the bleeding, and to comfort him. I tried to keep him calm. He seemed to recover for a while, but then he grew weak, and spots appeared all over his skin, like mosquito bites…

I felt very alone. I buried Sun-il. He had wanted to grow up to become a botanist. But he’d been forced to come to Japan, to work in the factories.

After a few weeks, I also became ill. My hair fell out, and I became bald… I was very weak. I felt angry that I had no control over my own body.

I recovered, and when the war ended, I returned to my hometown. But back in my homeland, I was an outsider because my Korean was not good enough. Then the Korean War broke out.

Returning to Japan, I did all that I could to hide my identity. If they knew what I was, it would be difficult to work and find a place to belong in society.

Today, I try to find meaning in what happened. But I only find absurdity.

Yes. It is the essence of absurdity.’

After I finish translating the document, I stand up and open the window. The room has suddenly become very stuffy. It feels suffocating and hard to breathe.

I gulp down the outside air.

Then I return to my bed, sit down, and pick up my camera again.

I hesitate for a long time before finally pressing the button, moving onto the final image.

Is this what frightened me so much?

There’s nothing in the frame except for Morimura’s documents, laid out on the floor, and the shadowy recesses under the bed.

I breathe out in relief. I realise that I’ve tensed up, and now I try to relax my shoulders, to slow my heart rate down, but my eyes are drawn back to the image.

There’s a strange and subtle sense of movement… At the back of the picture, in the shadows under the bed.

My chest tightens.

A miniature hand slowly creeps into sight, then another… Two ash-white hands, crawling cautiously forwards…

Hurriedly I switch off the camera. The screen goes black.

I don’t dare to breathe. I drop the camera.

But down, at my feet, a finger tickles.

I jump up, back away from the bed.

Slowly, two large hands inch into sight, the fingers waving and feeling ahead like the sensitive legs of a spider.

The hands are shy at first, tentatively becoming familiar with the floor, then they pounce forwards, and behind them the arms appear, stretching out.

The top of a bald head surfaces.

Morimura pulls himself out from under the bed and crouches opposite me. He looks down at the floor, hunching his shoulders, squatting.

Then he rises, straightening his shoulders, straightening his back, and his sad expression changes to one of calm.

I look into Morimura’s eyes and see that they are not eyes but holes torn through white flesh, opening out onto endless space; black as rain.

Editor’s Note on Hibakusha:

Hibakusha is not L.P. Lee’s first work to appear in Eastlit. Her previous published pieces are:

- The Man Root appeared in Eastlit January 2015.

- The White Fox was in Eastlit March 2015.

Editor’s Note on Hibakusha Artwork

The original artwork for this story is by Annie Ridd.